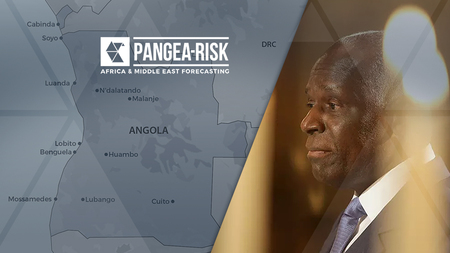

ANGOLA: POLICY CONTINUITY AND ENHANCED ECONOMIC PROSPECTS LOOM PAST ELECTIONS

Tue, 26 July 2022

With four weeks to go until the Angolan general elections, a dispute over the funeral and legacy of Angola’s former president is distracting from the ruling party’s campaign messaging of rising economic growth and falling inflation levels. Despite its popular appeal, the main opposition alliance is unable to capitalise on some of the discontent with the government and is failing to present a viable governing alternative. Re-election of the incumbent and continued state asset privatisation and economic liberalisation with IMF assistance remains the most likely scenario from August onwards.