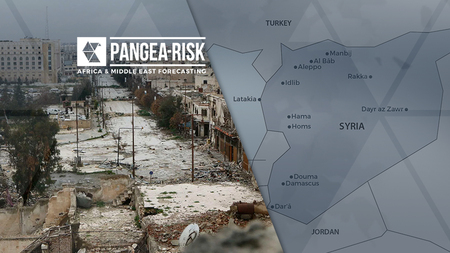

SYRIA: A ‘FROZEN’ CONFLICT RISKS ESCALATING DUE TO THE IMPACT OF THE WAR IN UKRAINE

Thu, 28 July 2022

Economic conditions in Syria have been mired by the prolonged local conflict, turmoil in neighbouring Lebanon, and now the war in Ukraine. Spiralling inflation, weaker government spending, and elevated political instability remain key impediments to a meaningful economic recovery. While violence has diminished since the peak of the conflict, a protracted war in Ukraine could disrupt the volatile status quo in Syria, potentially endangering ceasefire agreements, tilting the power balance, and complicating reconstruction and economic revival efforts.