SPECIAL REPORT: COUNTRIES TO WATCH IN 2023 – WORST AND BEST COUNTRY RISK PERFORMERS

Tue, 10 January 2023

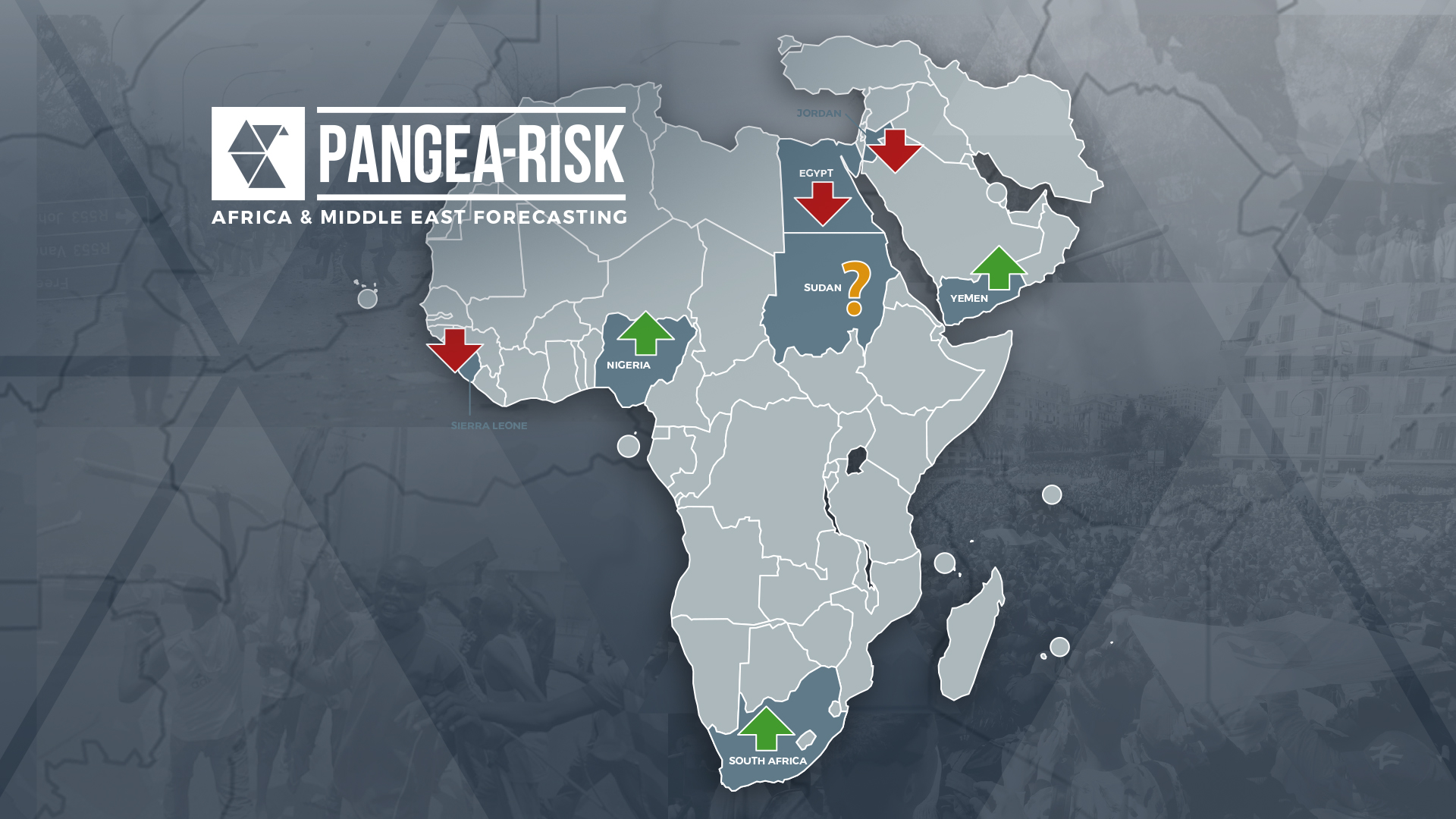

Two of Africa’s largest markets are set for a healthier 2023, based on our forecasts. Unavoidable economic reforms, a looming currency devaluation, and a crackdown on oil theft should improve post-elections Nigeria’s risk outlook. Meanwhile, South Africa’s president is running out of excuses not to address power outages, corruption, and economic reforms. In the Middle East, a peace deal may become reality as a tentative truce in Yemen continues to hold. However, rising debt in Egypt and stubbornly high inflation in Jordan and Sierra Leone may drive a significant deterioration in the country risk rating in 2023. Pangea-Risk picks its country risk “winners” and “losers” and reveals a “wildcard” country to watch for the year ahead.